Page Index

This series presents interviews of professionals in diverse fields who view Japanese culture from overseas. The interviewees are people the author has met through her work in publishing.

What unknown stories are to be found as we peel back the layers of tradition and culture?

Shanghai-based book planner and translator Tang Shi introduces Japanese culture to Chinese audiences. After studying at Hokkaido University, Tang began working for a publisher in Shanghai, where she translated and published Japanese books in Chinese on subjects ranging from literature to art.

Now a freelancer, Tang has planned, edited, and translated titles including Hana o tateru (Arranging Flowers; published by Shinchosha/Seika no Kai, 2021) by Kawase Toshiro, Boku no bijutsucho (Mon cahier d’arts; Misuzu Shobo, 2019) by Harada Osamu, and Chogeijutsu tomason (Hyperart “Thomassons”; Chikuma Shobo, 1987) by Akasegawa Genpei published in Chinese. It was a fortuitous encounter with a book that ignited her interest in Japanese crafts, which she writes about for the Chinese public.

唐詩 Tang Shi

Editor and translator based in Shanghai. Born 1991 in Zhejiang province. After graduating from Heilongjiang University, she attended graduate school at Hokkaido University, specializing in visual art and expression culture theory . Returning to China in 2016, she took a job with a Shanghai publisher, where she translated and published works starting with Iizawa Kotaro’s Shi shashin ron (A Study of the ‘I-photo’; Chikuma Shobo, 2000) and moved on to a series of literary works by Terayama Shuji and Shibusawa Tatsuhiko, the novel Anarogu (Analog; Shinchosha, 2017) by Beat Takeshi, and collected interviews with artist Nara Yoshitomo. Went freelance in 2022.

Our First Meeting

I was introduced to Tang by Paris-based artist Onodera Yuki. Onodera, recipient of the Nicéphore Niépce Prize, France’s most prestigious prize for photography, and whose principal work is the series Furugi no potoreito (Portrait of Second-hand Clothes; 1994), became acquainted with Tang after exhibiting her works in Shanghai. One autumn day in 2018, Tang came to my office, then located in the 3331 Arts Chiyoda building. To my great surprise, Tang had written to me about her visit, and conversed with me, in virtually perfect Japanese. I asked her where she had learned Japanese. With no contact with the Japanese language until graduation from her university in China, Tang said she learned the language during the three years she spent as a foreign student at Hokkaido University’s graduate school, where she had studied the “I-photo.” She related that thanks to her fluency in Japanese, her employer assigned her to translate and publish Japanese works and handle product planning as part of her editorial job in Shanghai. We got along well at our meeting, and Tang has become a respected friend.

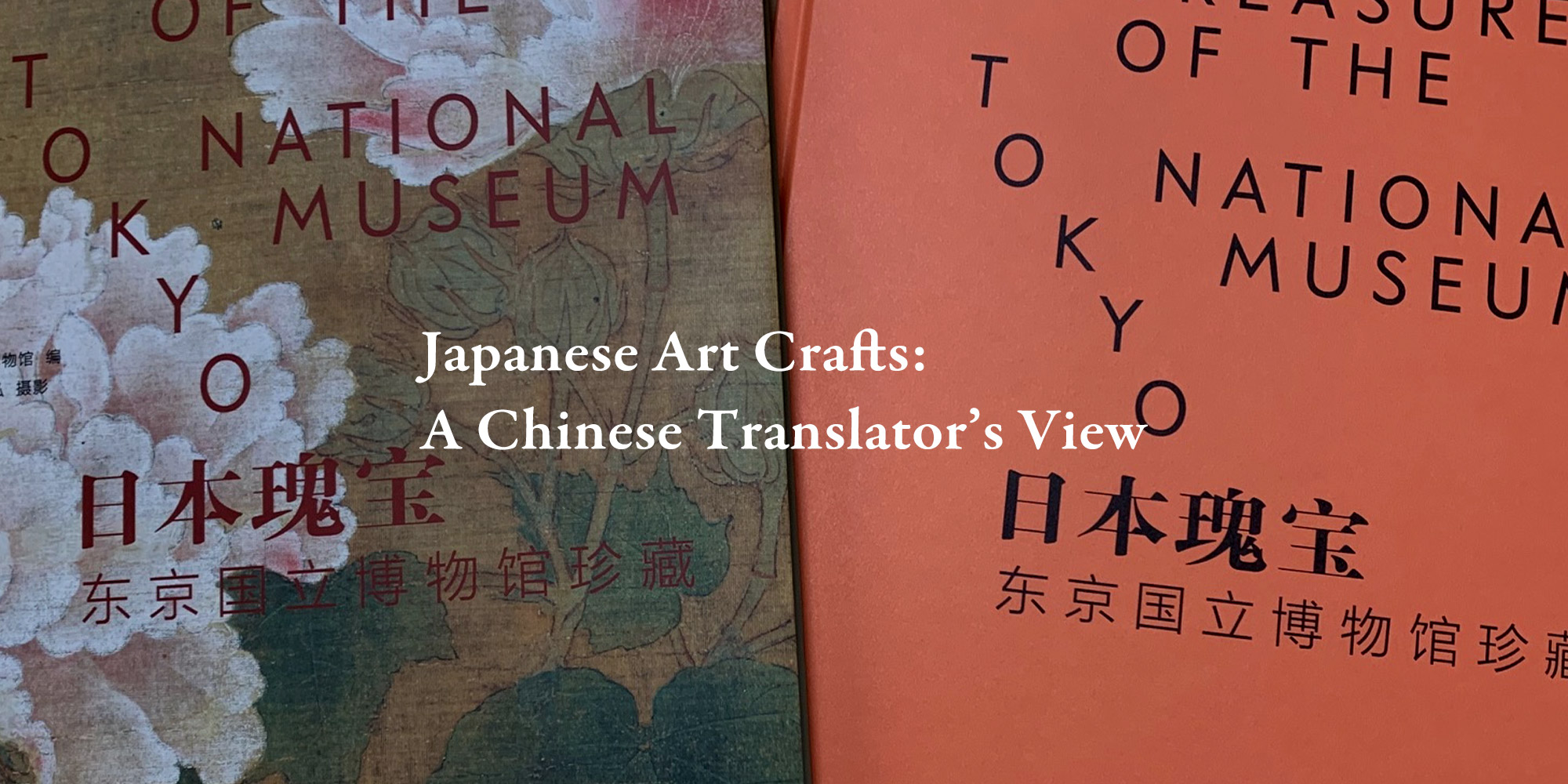

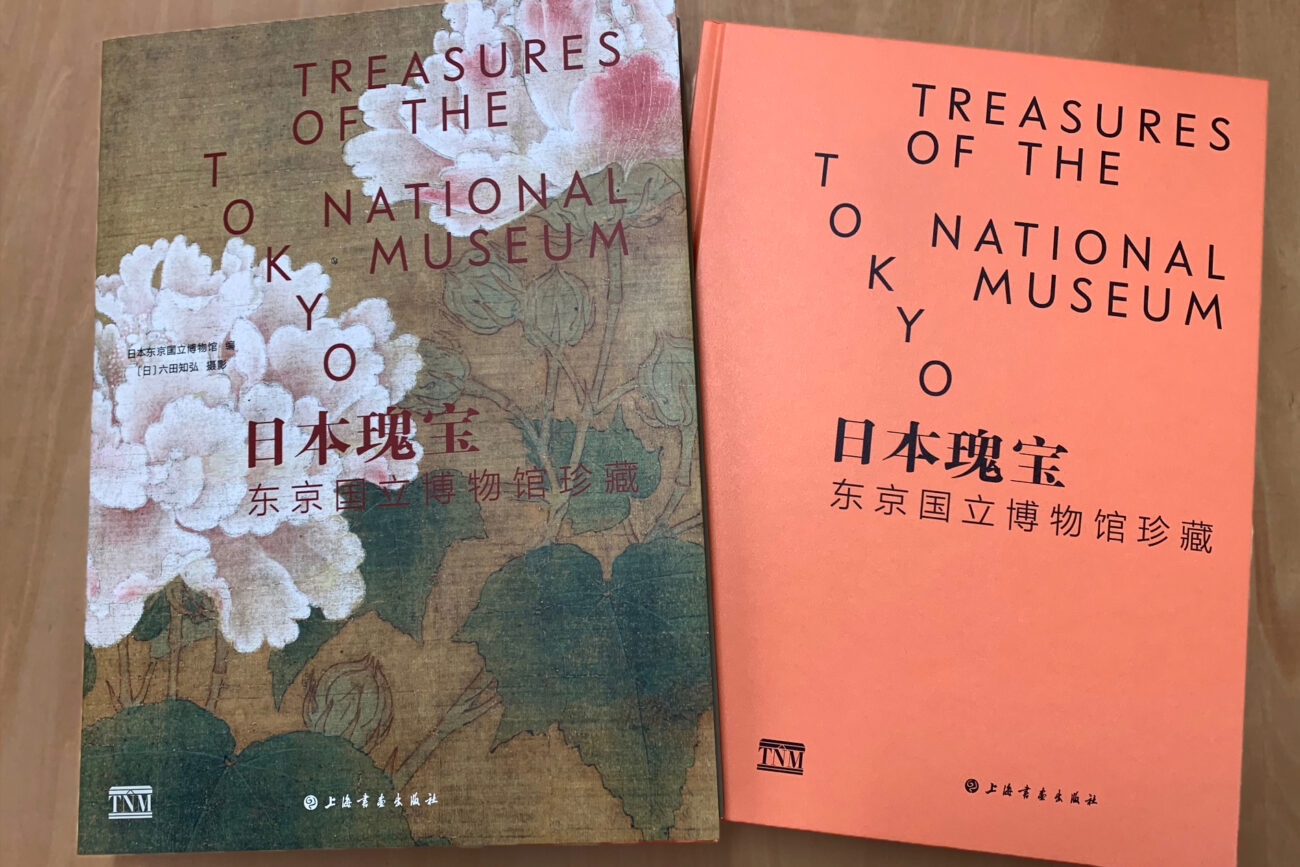

Treasures of the Tokyo National Museum Published in Chinese

Right around that time, I was in the final stages of preparing Tokyo Kokuritsu Bijutsukan no shiho (Treasures of the Tokyo National Museum; Bookend Publishing Co., Ltd., 2020), a project I had worked on for seven years. The publication of the book, a collection of 150 photos principally of the museum’s national treasures and important cultural properties selected by photographer Muda Tomohiro, was timed to coincide with the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games. Intended to introduce non-Japanese visitors to the allure of Japanese crafts, editions in Japanese and English were planned and the book design was done in Paris. After my meeting with Tang, it was decided to also publish the book in Chinese.

By chance, the publisher where Tang was working at the time focused on translating and publishing works on Japanese crafts. Tang also had extensive experience in book production and broad knowledge thanks to her contacts with writers, so I asked her to act as a go-between with a respected art book publisher in Shanghai and concluded a copyright agreement with that company. From that point on, she handled everything from editing to delivery with competence and efficiency, and the Chinese edition came out without any difficulties.

But due to the Covid-19 pandemic-triggered recession, Tang’s employer had to cut its work force and reorient its focus. As a result, planned projects related to Japanese culture that Tang had hoped to work on were cancelled. Nonetheless, the company piled work on her and she was having to work two or three times harder than before, so in 2022 she decided to go freelance. Now her days are filled with translation projects, as well as editing, interpreting, and writing. In September 2023, once Chinese were able to resume travel abroad, I interviewed her when she came to Japan after a three-year absence.

What brought about your interest in Japanese crafts?

After completing graduate studies at Hokkaido University, I took a job in publishing in Shanghai. I was assigned to produce books on Akagi Akito, Mitani Ryuji, and other artisans as my main work, so I gradually picked up more knowledge about Japanese crafts.

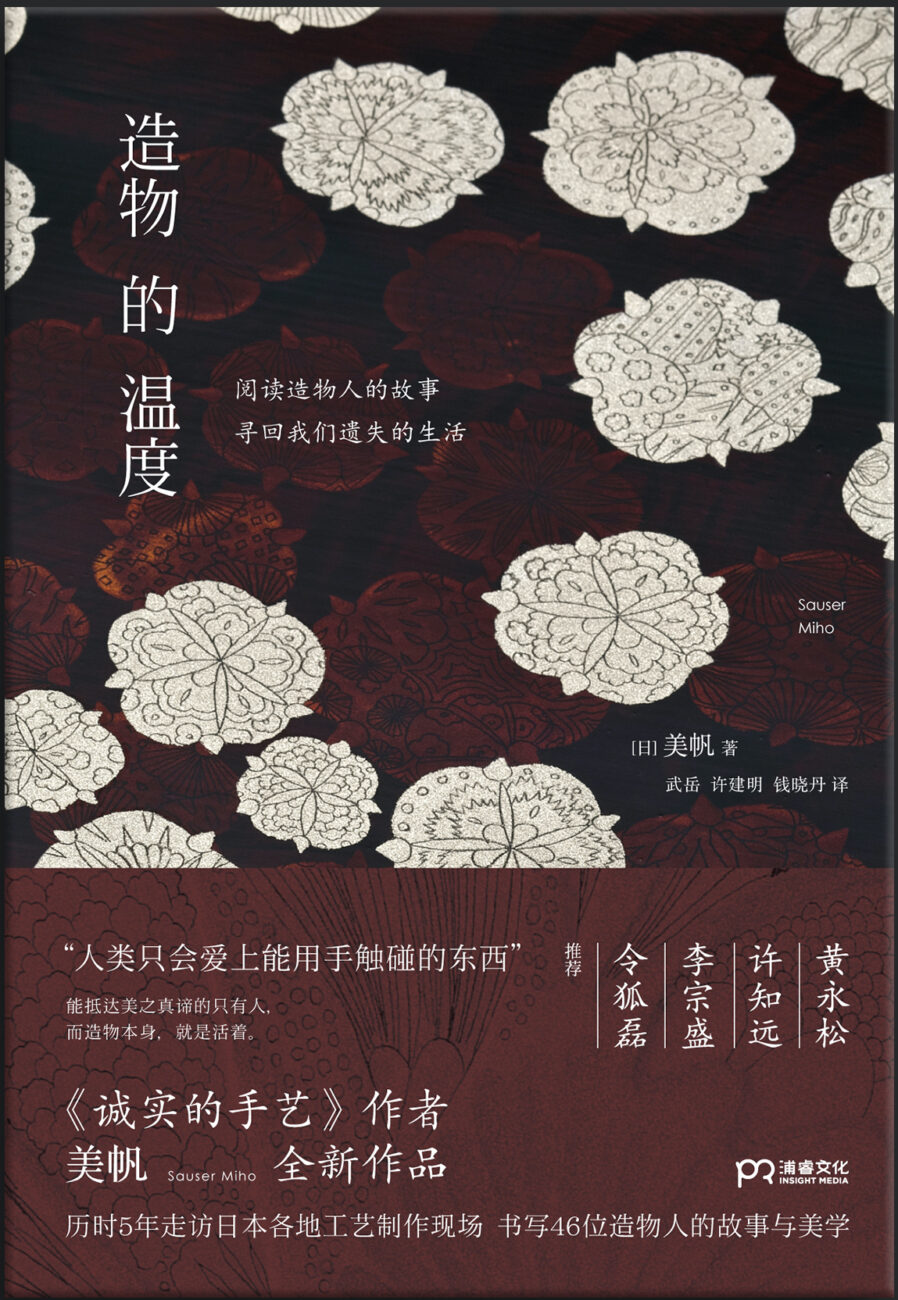

My interest grew even stronger after I met Sauser Miho, author of Zao wu de wen du (The Temperature of Handmade Things; Purui Culture, 2020). Sauser had been interviewing Japanese artisans for decades and publishing her writings in Chinese magazines. The Temperature of Handmade Things was a collection of her articles written over several years compiled in book form, and it was through editing that volume that I became fascinated by Japanese crafts.

Through introductions by Sauser, I went on to translate the official website for Kiryu textiles and Yondai Tanabe Chikuunsai: Shu-ha-ri (Chikuunsai Tanabe IV: Shu Ha Ri), published by Bijutsu Shuppan-sha in 2021, featuring the works of the renowned bamboo artist, adding to my experience translating about Japanese crafts. My knowledge benefited further from acting as interpreter for Japanese artisans invited to Shanghai for exhibitions and two-day talk shows by Qianjiang Culture, a Shanghai gallery selling Japanese crafts.

What do you think are some differences between Chinese and Japanese crafts?

Japanese crafts are diverse, extending from the making of tools and implements of daily life to ornaments and decoration. The artisans who create them are particular about materials and techniques. They do not simply make an article; they imbue it with their own thinking. In particular, they always keep users in mind, creating articles that are durable and adaptable to modern life. As expressions of Japanese aesthetics, their creations are beautiful as well as practical.

There are also people, not only artisans but also leading cultural figures and others who think deeply about the concept of craft, so compared to China, Japan offers a favorable environment for crafts. In addition, many shops selling crafts are long-established businesses knowledgeable about the history and techniques of their wares. They are trustworthy dealers who offer many reasonably priced items.

What are conditions like for craftwork in China today?

In China, meanwhile, some fine crafts were costly items intended for emperors and royal palaces, placing them out of reach of ordinary people. Today, the same is true of some designer art and brand products; they occupy a rarefied space having nothing to do with the lives of the majority.

Meanwhile, the crafts of making items for daily life have not developed. The absence of younger people to carry on traditional skills also means that crafts do not become better known and slowly die out. Ceramics is the only craft of items of everyday use that flourishes nowadays, especially for ware in connection with China’s culture of tea. Jingdezhen, long known for its production of porcelain, has become a popular tourist destination over the past few years. Many art school graduates have settled there too, breathing new life into the craft. The number of brands selling porcelain in pop-inspired designs to young people has also increased.

Many of China’s traditional crafts were made in state-run workshops. For ceramics, the state-run kilns, created to produce ceramics for the rulers of the country, were the most prominent example. As such, unlike Japan’s mingei folk crafts, which were made as part of ordinary people’s daily lives, China’s were quite different. The craft items made reflected the personal aesthetics of the emperors rather than the tastes of the populace. They were not created to be easy to use but were intended to symbolize luxury and project the power of the Chinese empire. Artisans were given no space to exercise their own thinking or taste; they had to submit to the dictates of the emperor.

Changes in government have a major impact on craft industries and can even lead to the loss of technologies. Artists and artisans are employed by the state to practice their crafts. When they can no longer work, many of them return to their villages and become farmers. They do not enjoy a recognized status in society, as do their counterparts in Japan, that allows them to pass on their culture and techniques, and I would say that is why China lacks long-established shops or lineages of artisans specializing in traditional crafts.

China does have innumerable folk handcrafts which continue to be made, particularly outside major cities and in the traditions of ethnic minority peoples. But these have a strong regional character, which makes broadening the market for them difficult, and they are always in danger of disappearing. Such factors may explain why interest in passing on or propagating crafts is weak in China compared to Japan.

How interested are young Chinese in crafts?

Most craftworks in China, including ceramics by noted artists, are prohibitively expensive, so young people have little interest in them. (laughs)

In cities like Jinhua and Dongyang in Zhejiang province, south of Shanghai where I live, the craft of woodcarving is more than ten centuries old. The two cities are famous for elaborately carved craftworks and furniture, but such items no longer exert much appeal in the lifestyle of the younger generation. Nowadays, they are only seen in the homes of the wealthy or in hotels or restaurants. Few efforts are being made, moreover, to pass on craft techniques or to spread information about them, and examples of Dongyang wood carving, which is also an important cultural property, have literally become museum pieces.

On the other hand, more and more people are starting to buy handmade trinkets. Markets for such handcrafted goods are quite lively, and while young people may feel that traditional art crafts are not part of their lives, they are attracted by the notion of things made by hand.

In terms of trends, art school students who have studied abroad, or young people well versed in what is going on abroad, have awakened to the appeal of crafts, and many of them want to work as artisans. But rather than having an interest in the traditional art crafts and folk crafts of China, they seem to be making artistic pieces in the field of crafts or simply pursuing art. Many of their works show little traditional or regional flavor, but I don’t think that is necessarily a bad thing. Working in crafts means that you first have to learn about materials and techniques, which can help pass down and propagate those crafts.

What are some of the difficulties you have encountered in Japanese-to-Chinese translation?

Japan has been heir to and adapted Chinese influences in many areas in addition to crafts. But although Japanese crafts may bear names indicating Chinese provenance, there are subtle differences, and one difficulty with translation is how to convey those differences appropriately. When I first started working as a translator, I believed it was better to use existing Chinese terms so as to make the content relatable to ordinary people and not just to experts in the field. But I realize now that this was not the right approach, so nowadays I often use Japanese terms for objects or ideas and supplement them with copious footnotes.

Take tokonoma (床の間), the recessed alcove found in traditional Japanese rooms. The standard translation for this in Chinese is bikan (壁龕), which in China refers to a recess in a wall for housing a Buddhist statue or image. Nowadays, however, it is used as the word for the niche in a shower stall to hold shampoo and so forth. Tokonoma, on the other hand, is a feature found only in Japanese architecture, so I believe it is incorrect to use bikan as the equivalent, as that word refers to something completely different. In such a case, I retain the kanji/phonetic letter combination for tokonoma and provide an explanation in a footnote.

Here is another language-related difficulty. Words in Japanese can be written with kanji only, a combination of kanji and the hiragana phonetic alphabet, or hiragana alone. Using one or another of these forms can yield words with completely different meanings. But Chinese uses only kanji, so it is very difficult to transfer the distinctions expressed by the Japanese orthography. I recently translated Kawase Toshiro’s Hana o tateru, mentioned above. Words like tatehana たてはな, rikka 立花 or hana o tateru はなをたてる—all meaning arranging flowers—appear in the work. Since all are rendered in Chinese as 立花, I had to be creative in explaining the different words so that Chinese readers would understand correctly.

Fortunately, books on crafts usually contain many photos or other visual images, so those can be used to supplement the text. China and Japan also share similar aesthetics, and in many cases, photos can communicate the intended meaning of the words.

What is your personal favorite quality of Japanese crafts?

What I like best about Japanese crafts is how they add an element of enjoyment to daily life, for example, making food or drink look more appealing, or created with a specific situation of use in mind.

I once sipped Japanese sake in a small guinomi drinking cup created by lacquerware artist Yamagishi Shodo. Made entirely of lacquer, the cup felt soft in my hand and enhanced the sake’s flavor. That sensation brought me happiness and made a strong impression on me that differed from anything I have experienced before.