Page Index

We believe that for local communities, crafts are hidden treasure that will prove to have value far greater than ever before. How will work that is grounded in nature and the environment be transformed and lifted as culture?

There are people who are putting into practice new perspectives and methods. In this series, we go to see these people at work, and we consider how makers and the people who connect them to markets are discovering new value in crafts.

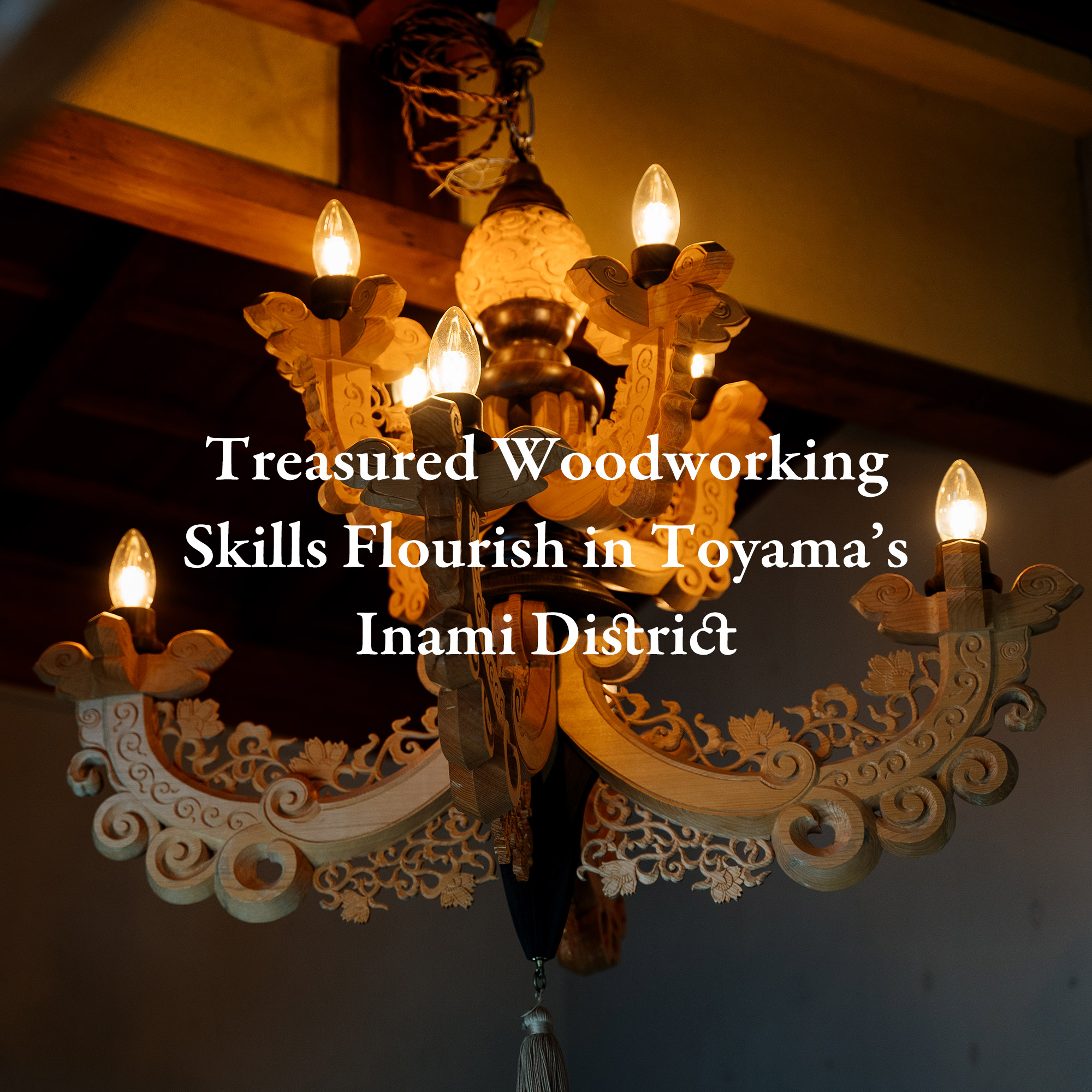

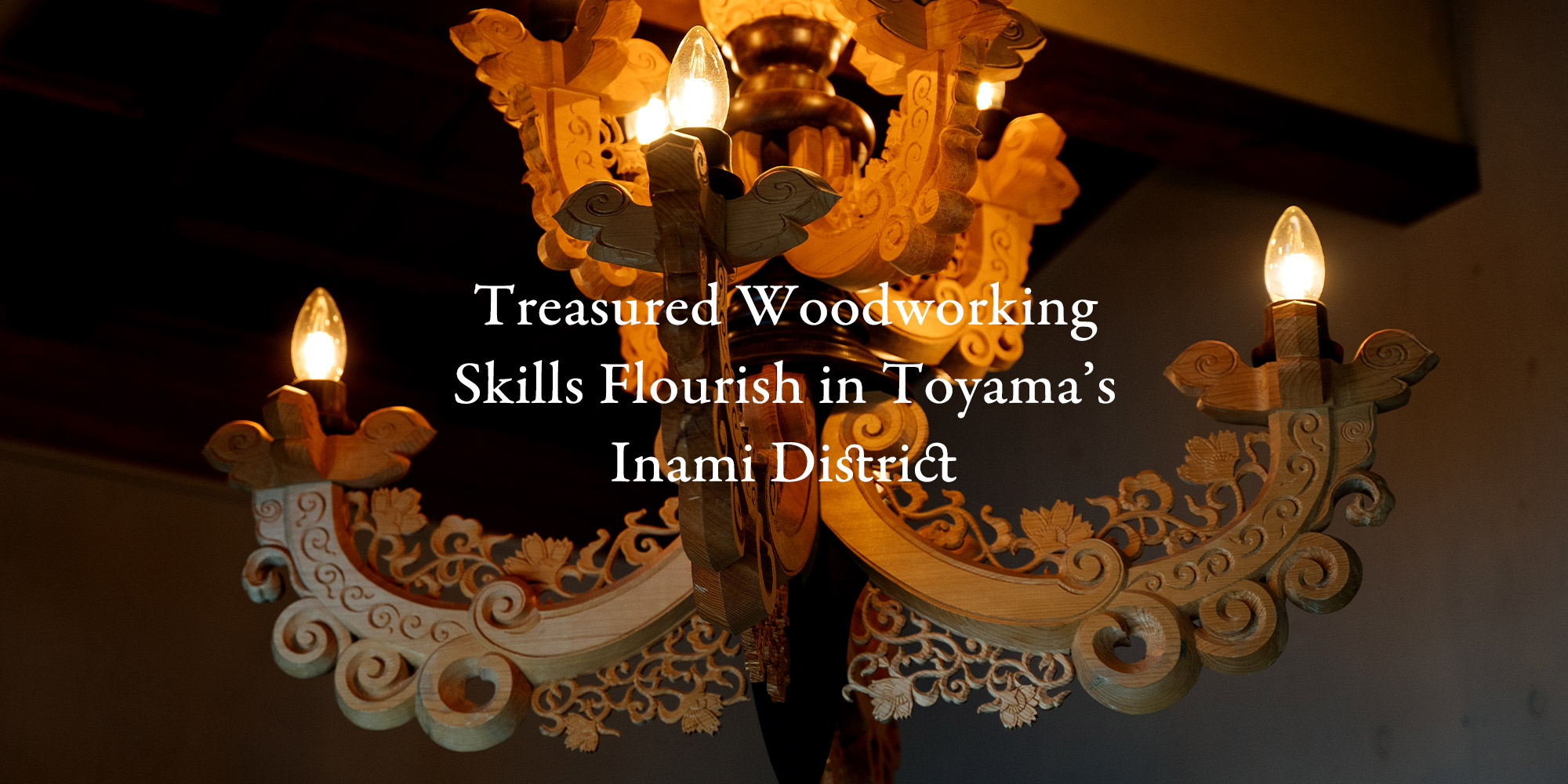

Traditionally, the craft of woodcarving evokes household status symbols such as an eagle—associated with power and courage—in a tokonoma or intricately carved ranma woodwork in the transoms of Japanese-style rooms. But nowadays the craft is being applied to modern furnishings and interior décor. In Inami, where woodworking has a long tradition, a series of new lodgings and shops have opened in the past few years. I visited the area last winter to learn about this new trend gaining momentum in Inami.

Photo: Ken Ohki

Inami: Cradle of Woodcarving Craft and Heartland of Faith

The sharp thwack of mallets reverberates from the depths of the houses along Yokamachi-dori: the sound of artisans at work. The traditional-style structures lining this street that is the approach to the Buddhist temple Zuisenji are not inns but the studios of woodcarvers.

With over 100 artisans carrying on their profession in this district of Toyama Prefecture’s city of Nanto, Inami is a rarity. No other part of Japan continues production of handcrafts on such a large scale.

The Hokuriku region has long been the heartland of the Jodo Shinshu school of Buddhism, whose teachings inspired widespread popular devotion. When Jodo Shinshu adherents rose up against powerful local personages in the “Ikko Ikki” rebellions of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Zuisenji became their headquarters. The temple was burned to the ground several times during such popular uprisings, but was rebuilt each time. It is said that the craft of woodcarving in Inami got its start in the 1760s, when woodcarvers sent by the temple’s headquarters at Higashi Honganji Temple in Kyoto helped with rebuilding the temple halls and shrines and taught the local carpenters their woodworking skills.

Those skills advanced further as local artisans went on to apply what they had learned to create artful transoms and woodwork for ordinary homes, as well as decorative objects such as sculptures of Tenjin, the deity of learning and scholarship. They were able to carve amazingly detailed works such as plum blossoms, pine trees, and dragons ascending to the heavens using only the simplest tools. When I visited Zuisenji, a temple attendant told me that even today many people in Inami are devout Buddhists and that locally carved Buddhist altars have pride of place in their homes.

Walking around the town, you will notice carved wooden ornamentation everywhere. Even though Inami is not an officially designated historic preservation area for traditional architecture, the facades of many buildings feature wooden doors and attractive latticework. It is obvious that local residents have voluntarily preserved the old townscape.

Photo: Ken Ohki

Apprenticeships Sustain the Woodworking Crafts

Inami is distinctive for two reasons. First, it is rare for one particular genre of handcraft to be concentrated in a single locale. Second, while many traditional crafts developed through collaboration in networks of artisans with different skills and roles, such division of labor did not catch on in Inami.

Each carving studio takes care of everything from obtaining the wood to carving, handling sales, and shipping the finished products. As a result, Inami woodcarving reflects the styles and tastes of its artisans and creators, who range in age from twenties to nineties. The carvers have all created their own niches and they are available for many different kinds of work.

Also, the age-old apprenticeship system is still practiced here. Aspiring artisans apprentice to an experienced older craftsman, helping out with the work under a five-year live-in arrangement. During this time, they also attend a training school run by the woodcarvers’ association, where they are taught by currently active carvers. At the end of their apprenticeships, they form same-generation professional groups. (The school closed March 2023).

In the past, the apprenticeship system ensured that artisans’ skills were passed on and developed throughout the country, but today there are few areas in Japan where it is still practiced. Even in Inami, it is doubtful whether the system can continue, given labor issues such as payment of the minimum wage and difficulties in accepting women as apprentices.

For now, the apprentice system in Inami remains vibrant, as budding craftsmen develop strong connections both with their older mentors and with fellow trainees. Rather than as rivals, they think of each other as fellows and collaborators, and they strive to encourage each other to improve their skills. These two distinctive features keep the backbone of the woodworking craft in Inami strong.

Photo: Ken Ohki

Bed and Craft, Where Guests Can Meet Artisans

Seven years ago, Yamakawa Tomotsugu, an architect living in Inami, created the Bed and Craft network, a group of properties where guests can stay or visit to spend time with works by specific carvers and creators.

“Local artisans create a whole range of items, from Buddhist images and traditional household woodwork to contemporary objects, but until now there was nowhere for them to interact directly with customers. Fine woodcarvings are expensive and not something a person would buy on a whim during a short trip. Bed and Craft gives visitors an opportunity to view works and develop relationships with creators by visiting their workshops. Later, they might commission a piece to mark an important occasion in their lives.”

Photo: Ken Ohki

In Inami, each of the Bed and Craft lodgings serves as a gallery for one particular artist. Bed and Craft calls this the “My Gallery” scheme. A portion of the accommodation fees paid by overnight guests is passed on to the artists.

Since opening in 2016, Bed and Craft has welcomed over 1,000 guests, 70 percent of whom are visitors from abroad. In Western countries, the tide of mass production has already pushed aside products made by hand, so the opportunity for visitors to see artisans at work up close is a valuable experience.

The Bed and Craft network lodgings include Tategu-ya, opened in 2016, Taë in 2018, and Kin-Naka, Mitu, TenNE, RoKu, and Tomoe, which all opened in 2019. As of May 2023, there are 11 network properties in all, including a reception facility and a restaurant. Exhibits feature not only woodcarvings but also Tanaka Sanae’s lacquerware at Taë, and the work of garden designer Negishi Arata at RoKu.

Photo: Kosuke Mae

Photo: Ken Ohki

The lodgings are not the former dwellings of wealthy merchants, as in many historic communities, but ordinary private homes. The luxury is that they are transformed into settings for displaying the world view and the works of a single artist. This sounds like an expensive undertaking, but a unique ownership system makes this possible.

Bed and Craft owners include travel agencies and foreign private investors wishing to own homes in Japan who have delegated the work of managing the buildings to Yamakawa. It is quite common in the case of major hotels for ownership and operation to be separate, but it is rare in small-scale operations.

Yamakawa explains that “what’s so interesting about Inami is that it’s a place where handcrafts are produced even today, and where everything is made by hand; no two products are alike. It’s rare for someone to be able to talk directly with an artisan, who can then conceptualize a piece from the ground up, so to speak.

“In the old days, though, everyone knew people who worked with their hands, and it was just natural to go to them and ask for work to be done. Users and artisans talking to each other led to improved skills and expressive methods. This is something that’s still possible in Inami, and to creators and architects like me, Inami is endlessly interesting. It feels as though things have come full circle.”

Photo: Ken Ohki

Woodcarving: Inami’s Lifeblood

I saw Tanaka Komei’s works for the first time at the Bed and Craft facility Tategu-ya, which serves as Tanaka’s gallery. Tanaka is an Inami woodcarver whose many works include conceptual female figures and seasonal items like hina dolls. When I laid eyes on his carvings of young women titled Tane, Hikari, and Mizu, it felt as though time had stood still. Mizu is a young girl with an almost translucent air and a gentle smile of indescribable lightness—she looked as if she might just fly off somewhere. Tane is filled with a sense of the divine, inspiring thoughts of prayer.

After graduating from Toyama Prefectural Takaoka Kogei High School, which focuses on training in industrial arts, Tanaka apprenticed to an Inami woodcarver starting around 1997. At the time, the woodcarvers’ cooperative had nearly 200 members. Under the system, prospective apprentices tour various studios before deciding which master to apprentice to. But generally, they have no idea of their masters’ personalities or work styles, so whether the match is a good fit is a matter of luck.

“Given that senior craftsmen exert so much influence on their apprentices, the choice of master can really affect the apprentice’s future,” says Tanaka. His master, who exhibited works at the prestigious Nitten art exhibition, encouraged him to work on his own pieces in the evening. Some apprentices readily pick up the skill of carving quickly and accurately, and soon become expert.

Photo: Ken Ohki

Apprentices who studied together at the cooperative’s training school maintain ties after becoming independent. If Tanaka receives a commission to carve a dog, he can refer the client to a colleague who is better at creating that kind of figure. In turn, a fellow artist may refer a client looking for someone to carve hina dolls to Tanaka. When the cooperative receives work for restoring cultural artifacts, several artisans may get together to perform the work.

“A restoration work team will consist of highly experienced carvers in their seventies and eighties, but also mid-career artisans in their thirties and forties. And invariably younger workers who are still learning their craft are included. Working as a team gives the younger people a chance to see and learn from veteran carvers, which is a way of preserving the skills and techniques of Inami woodcarvers.”

Although Tanaka works as a journeyman carver from time to time, his main line of work now is as a creator of original works. Nonetheless, he is firmly grounded in his identity as an Inami woodcarver.

“Personally, I’m not thinking of moving away from Inami to pursue my craft. I’ll often go to Zuisenji for inspiration if I’m feeling stuck, to gaze at the sculpted woodwork and try to figure out how it was done.” Zuisenji Temple is an unwavering presence that represents the very wellspring of Inami woodcarving. The history and culture of this place are inseparable from the craft of woodcarving.

Photo: Ken Ohki

When Restoration Work Is Needed, Inami Is Indispensable

Kin-naka, opened in 2019, was set up as woodcarver Maekawa Daichi’s gallery.

Maekawa Daichi is the second head of the Inami Wood Carving Craft Studio, succeeding his father, Maekawa Masaji, a woodcarver working on traditional themes who has exhibited at Nitten and has received a special prize for his work. Returning to Inami after having spent his twenties studying abroad, Daichi’s first impression was that woodcarving was a craft in crisis.

“A generation ago, there were 200 craftsmen in Inami. Now there are about 140, many of whom are elderly. Twenty years from now, I think the numbers will have dwindled by half.”

Photo: Ken Ohki

Maekawa’s strong sense of the value of Inami’s woodcarving craft is what impelled him to action. “As a place where woodcarvings are produced, there is probably no other place like Inami in Japan now. Other areas are well-known for woodcarving too, but they have only a handful of artisans left. I think that Inami is the only place that still has a sizeable contingent of craftspeople who can undertake large-scale restoration work.” Time spent abroad has given Maekawa the necessary perspective on the state of his craft in his hometown, and his gallery at Kin-Naka is replete with his love for Inami.

Photo: Ken Ohki

Photo: Ken Ohki

Photo: Ken Ohki

Photo: Ken Ohki

Demand for ranma, the carved transoms that were once a mainstay product of Inami woodworkers, is steadily declining as more and more homes are built without Japanese-style rooms. According to Maekawa, the future of Inami woodcarving may lie in two directions.

“One is classic woodcarving using traditional methods, in demand for restoration projects such as, for example, the Honmaru Palace daimyo residence at Nagoya Castle. Only Inami can provide a sufficient number of artisans who can meet tight completion deadlines. The other is production of goods for household use. Ranma, which evolved from shrine and temple woodcarvings, gradually found their way into ordinary homes, so we may have a path forward if we can create items that suit today’s lifestyles.”

Maekawa works anonymously as a professional woodcarver but also puts his name to works he makes as an artist. The cloud-shaped chandelier hanging at Kin-Naka (see photo at beginning of this article) is one of the Maekawa’s most impressive pieces of work, a fine combination of highly skilled carving and creativity. This coming together of skill and art expresses the new products coming out of Inami.

“Inami still preserves its unique local production ecology—from the people who make the carving tools to the lumbermills that process the wood we use. Last year I was working on something that required creating very deep curvatures. Forging a new tool just for that would be very expensive, so I went to an elderly shrine carpenter to ask how I should handle the task. He was quick to reply that I could accomplish what I needed to do using the usual tools, but that I needed to use them in a slightly different way. Benefitting from everyone’s skills and experience is how we work here in Inami.”

A World of Authenticity

“Inami’s great strength lies in the large number of craftsmen and the high level of skill they bring to their work.” So says architect Yamakawa, who believes that what is happening there is beginning to match the trend of discerning people being particular about the items they choose.

“In the old days, when seasonal gift-giving was more commonplace, people placed a lot of importance on the wrapping paper in which their gifts were wrapped, putting their faith in the status and peace of mind that came from patronizing a prestigious department store. But nowadays, when everyone has all kinds of information at their fingertips, brand names and surface appearances have lost their value. Now people are looking for authenticity; they pay much more attention to where an article came from, who made it, and how it was created.”

Photo: Ken Ohki

Pieces made by artisans in a place with a well-established history of the craft; one-of-a-kind items created by people you have met and with whom you have established a relationship—such items no doubt have much more value than standardized products.

“3D printers and the like are fine for making identical goods. But I feel that handmade objects are those that will last and will be treasured. Local characteristics, the culture those objects derive from, and context are important. Who is carving the wood, and where did it come from? Why was it made in this particular place? These aspects will continue to constitute elements of the local culture.”

There is a reason why crafts and handwork develop in certain places, but no new path can be forged without a foundation of history and skills, which in turn is the only future for local culture.