The beauty of a work of craft has a story behind it. Surely that story is what will shape the next generation. We will search out the outstanding work created by hands and hearts and report about what is happening in the world of craft today.

Page Index

Message from a Bamboo Installation

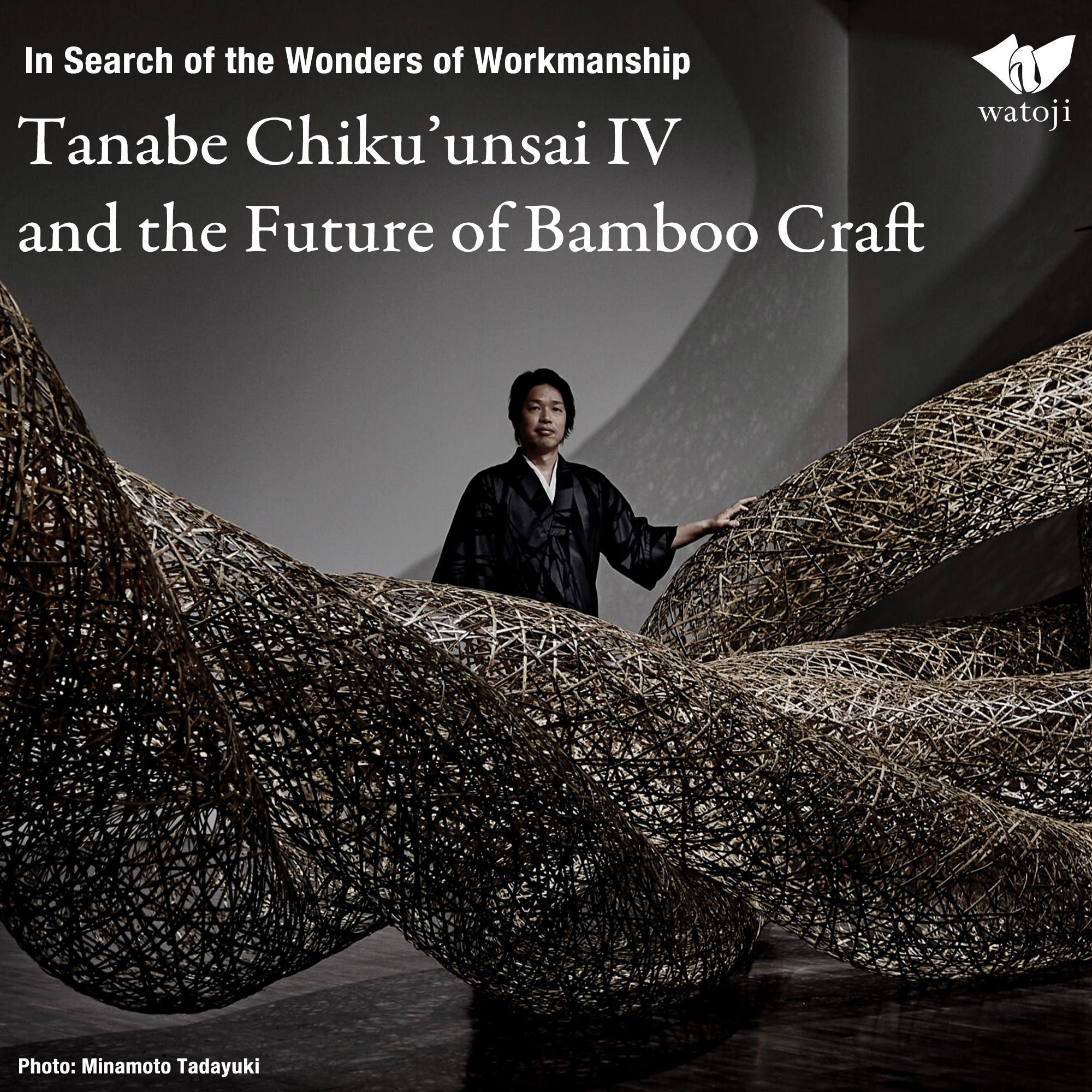

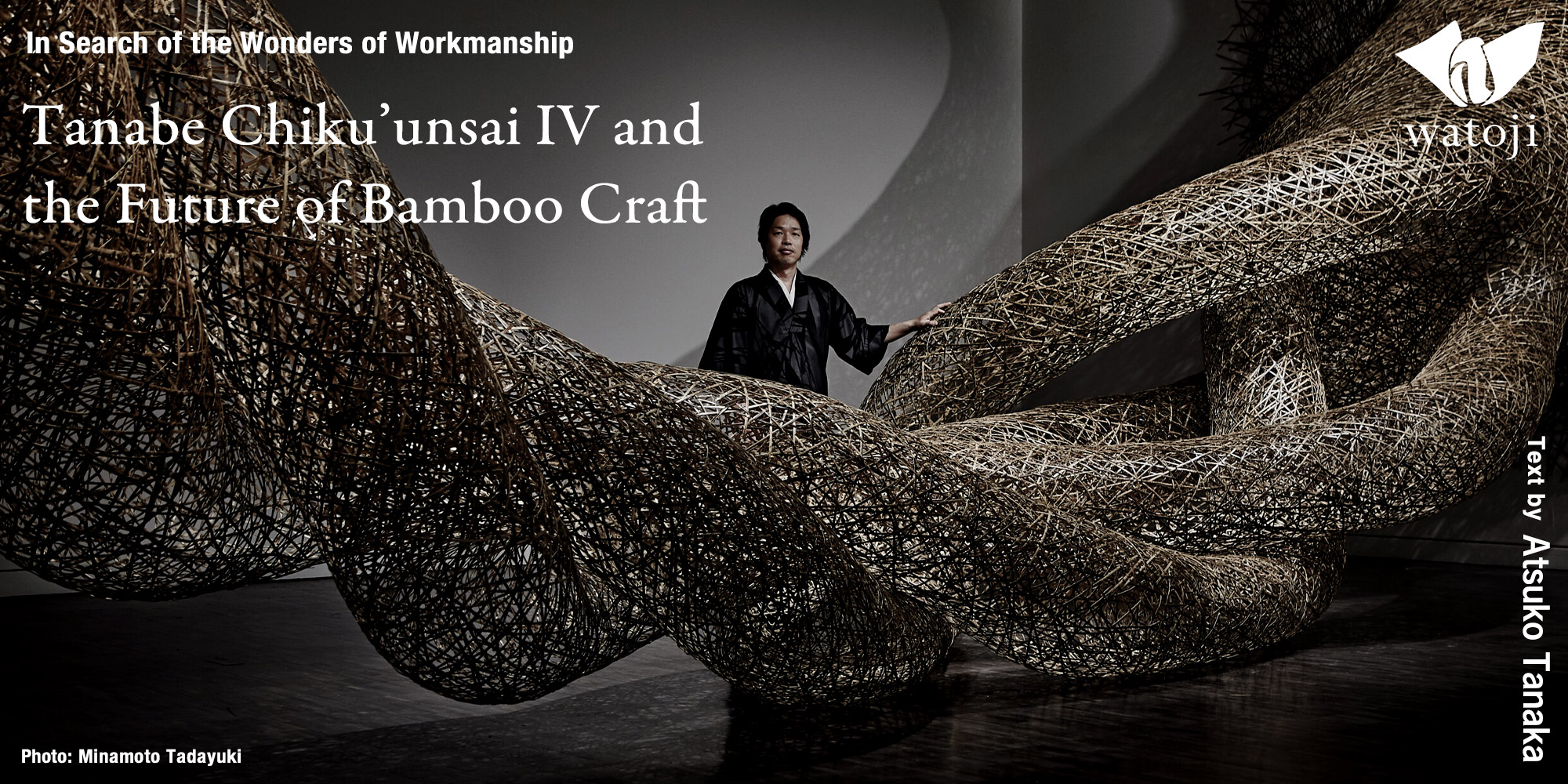

Twisting, spreading, crawling, rising like a dragon or a giant serpent. A tall assemblage of bamboo reaching for the skies, pulsing with life force and expanding the possibilities of thin strips of bamboo stimulates the viewer’s imagination.

Tanabe Chiku’unsai IV’s installations have gone far beyond the bounds of bamboo craft, dazzling the art world and pointing the way to new possibilities for the “Asiatic” material that is bamboo. What makes this work so distinctive is its power and originality. Born into a family of traditional bamboo artisans, Chiku’unsai has created an innovative example of bamboo craft using individual bamboo strips prepared by hand according to methods that pass down the traditions of his forebears.

Tanabe Chiku’unsai IV

Born as the second son of Tanabe Chiku’unsai III in Sakai, Osaka prefecture in 1973. After studying sculpture in the Department of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts he studied under his father, Chiku’unsai III, mastering the craft and earning accolades in the world of traditional crafts. He has also created large bamboo installations displayed in many museums abroad. He assumed the name Chiku’unsai IV in 2017.

©Minamoto Tadayuki

©Minamoto Tadayuki

The shape of this mega-scale objet created solely by bamboo weaving and plaiting techniques connects with the universe and life that are eternal themes of East Asian philosophy, but it also has a broader message. Chiku’unsai says: “People who love bamboo like me don’t want to think of it as a mere object to be used up and thrown away. We want to find some way of recycling each and every strip that I split and shape so carefully with my tools.”

At the conclusion of an exhibition, Chiku’unsai’s work is dismantled, strip by strip. Damaged strips are discarded, the remainder slated to be reused for the next creation and supplemented with new strips as needed. Chiku’unsai uses natural materials and works by hand. Recycling the bamboo strips, like living cells, is what makes his installations so contemporary. While freely imbuing them with the quality of art, he reveals his love for bamboo and the pure heart of a person raised in a family of bamboo craftsmen.

Today, the bamboo weaving craft is practiced most widely in Oita and Tochigi prefectures, both of which are known as bamboo-producing areas. Sakai, the Osaka prefecture city where Chiku’unsai has his studio, formerly produced bamboo and supported a thriving bamboo craft industry. But in contrast to its development in other regions, the history of bamboo craft in Sakai was heavily influenced by its status as a self-governing city that prospered through trade. From around the middle of the Edo-period (1603–1868), the culture of sencha (appreciation of steeped green tea) was imported from China and became popular mainly among Osaka merchants and literati, who gathered to drink green tea and admire Chinese-made baskets for displaying flowers. Their connoisseurship of these baskets led to the birth of bamboo craft in Sakai.

The culture of sencha appreciation became popular in Osaka in reaction to the formality of “way of tea” (sado or chanoyu) gatherings, which had become increasingly laden with elaborate etiquette and set procedures from the birth of the art during the Momoyama period (1573–1615) through to the Edo period. The more informal atmosphere of sencha, together with their attraction to Chinese literati culture, was better suited to these merchants’ disposition. Bamboo is strong and flexible, and paintings and calligraphy depicting bamboo as well as utensils made from it were much prized. A plant that rose in such a stately and vibrant silhouette, and yet in hollow and light-weight stalks soaring high in the sky, represented a kind of ideal for the Chinese literati, who enjoyed bamboo as a subject and as a motif in their arts. The Osaka merchants who gathered to drink sencha naturally fell to imitating the cultured Chinese they so admired, and they particularly prized the delicately woven bamboo flower baskets that were imported from China.

According to Chiku’unsai, “at the time, there were no finely worked bamboo articles in Japan, and those who appreciated the Chinese bamboo work decided to imitate the superb Chinese techniques, a movement that centered on Sakai.”

Sakai bamboo craft, which developed in response to the requirements of sencha aficionados, is therefore something of an urban craft. As befits an urban craftsman, Chiku’unsai I was not merely a master bamboo weaver, he also headed the Shofu Seizan-ryu school of flower arrangement, assiduously attended cultural gatherings, and polished his accomplishments. Concentrating on his craft but also broadening his horizons, Chiku’unsai seamlessly melded the two elements in his persona to become a new type of craftsman. This quality he passed on to his successors. Chiku’unsai IV’s installations reflect the fruition of this orientation. His works have been well received both at home and abroad, and with steady demand to hold exhibitions, he continues to progress.

Many Sakai bamboo craftspeople, buffeted by the rise and fall in their fortunes, abandoned their craft. Today in Sakai, only the Tanabe family remains, and Chiku’unsai IV is determined to carry on the family tradition. The family motto, “Tradition is an ongoing challenge,” could feel like a burden, but Chiku’unsai views it instead as a springboard for transforming his craft into art, an encouraging message for anyone working in crafts.

Overcoming Obstacles, Forging a Path to the Future

But Chiku’unsai keenly feels the fate of his craft today, because it has become increasingly difficult to obtain materials. Bamboo was plentiful around Sakai in the past, and as the city was rebuilt out of charred ruins after World War II, bamboo craft enjoyed a resurgence. But groves outside the city were cut down during riverbank improvement works along the Yamato River, which flows into Sakai Bay, and local bamboo craftsmen were forced to source their materials from farther afield. In previous times, bamboo had been widely used for everything from building materials to farm tools. Fine-quality bamboo was available throughout the country, and it also sustained the bamboo crafts in Sakai.

But today, when plastic has long since supplanted bamboo as the material used for everyday articles, bamboo production has reached a crossroads. Growers are increasingly unable to find users for their product, groves are being abandoned, and what few caretakers are left are aged. Groves producing the type of fine-quality bamboo used for bamboo weaving have been rapidly disappearing. Chiku’unsai believes that “in the future, it will not be enough to pass on my skills. I will also need to become more actively involved in preserving bamboo itself.”

©Minamoto Tadayuki

Chiku’unsai currently sources his bamboo from seven different locations around the country. The Japan-native madake, which is known for its fine, strong, and flexible fibers, comes from Kagoshima, Fukuoka, Oita, and Shiga prefectures. Wakayama supplies kurochiku, a dark-colored bamboo whose color deepens with exposure to winds off the ocean. Torafudake, known for the tiger-striped pattern appearing when the bamboo is heated and polished, comes from Kochi, where it grows only in certain groves in the Awa area of the city of Susaki. Hobichiku comes from Tottori. It is a nemagaridake or bent-root bamboo native to the area from long ago. With the future of these varieties in mind, Chiku’unsai has been helping ensure the preservation and revival of bamboo groves.

He travels to various parts of Japan to research the types of bamboo growing there, holds local workshops, and makes regular, large purchases of bamboo from locales where the lack of workmen makes it difficult to continue upkeeping the groves. He holds webinars with producers to keep collectors and curators overseas abreast of how bamboo is faring in Japan. Given how busy Chiku’unsai is with creating new works, these additional activities are demanding. But he is painfully aware that not only bamboo craft but other traditional crafts are also on the verge of dying out. He is on a one-man mission to make sure that does not happen.

Chiku’unsai is convinced that “the fact that my installations use huge amounts of bamboo is key to reinvigorating the groves where it grows.” Demand for bamboo would grow substantially if it were used more extensively in buildings, which would ultimately guarantee the stable upkeep of the groves. Entering into an agreement with luxury fashion brand Loewe to create installations will surely lead to interesting concepts.

The Chiku’unsai studio currently has more than ten apprentices, each of whom is acquiring solid skills according to a graded license system. Chiku’unsai explains that this teaching program is based on a ten-year system, with students advancing to various skill levels at three-year intervals, when they are tested. If successful in advancing to the next level, their achievement is recognized with a ceremony. This gives apprentices a clear-cut guide to their progress.

Chiku’unsai intends to gradually increase the number of people studying under him. He also has three children; they are rapidly growing up, sometimes helping him with his installations and workshops. To ensure that the craft of bamboo weaving continues when his children come of age, Chiku’unsai is never short of ideas and energy to help the craft survive and thrive.

Tanabe Chiku’unsai IV official website:

https://chikuunsai.com