Page Index

The beauty of a work of craft has a story behind it. Surely that story is what will shape the next generation.

We discover outstanding work created by hands and hearts and report about what is happening in the world of craft today.

More than twenty years ago I wrote a book about craftspeople and crafts with traditions going back to the Edo period (1603–1868)(1). The artisans were highly skilled and their works were utilitarian and beautiful. The opportunities to interview them about their lives before and during World War II were invaluable experiences, and I was heartened to sometimes encounter the next generation of artisans passing on time-honored skills and techniques into the modern world. Today many of the artisans I interviewed for the book have passed away.

The interviews allowed me to feel first-hand how the new generation of artisans differed from their predecessors of the days of traditional craft apprenticeship, when nothing was taught explicitly: apprentices were expected to learn by watching their uncompromising masters and to rely on their own intuition and experience in acquiring and refining their skills. Regarding the problem of successors, which had already become a serious issue by then, younger artisans are more flexible. They realize that there are avenues for crafts to thrive without clinging to the old apprenticeship system and cottage-industry traditions.

(1) Edo no tewaza chan-to-shita hito, chan-to-shita mono (Reputable Craftspeople and Reputable Crafts of Edo). Tokyo: Bunka Publishing Bureau, 2001.

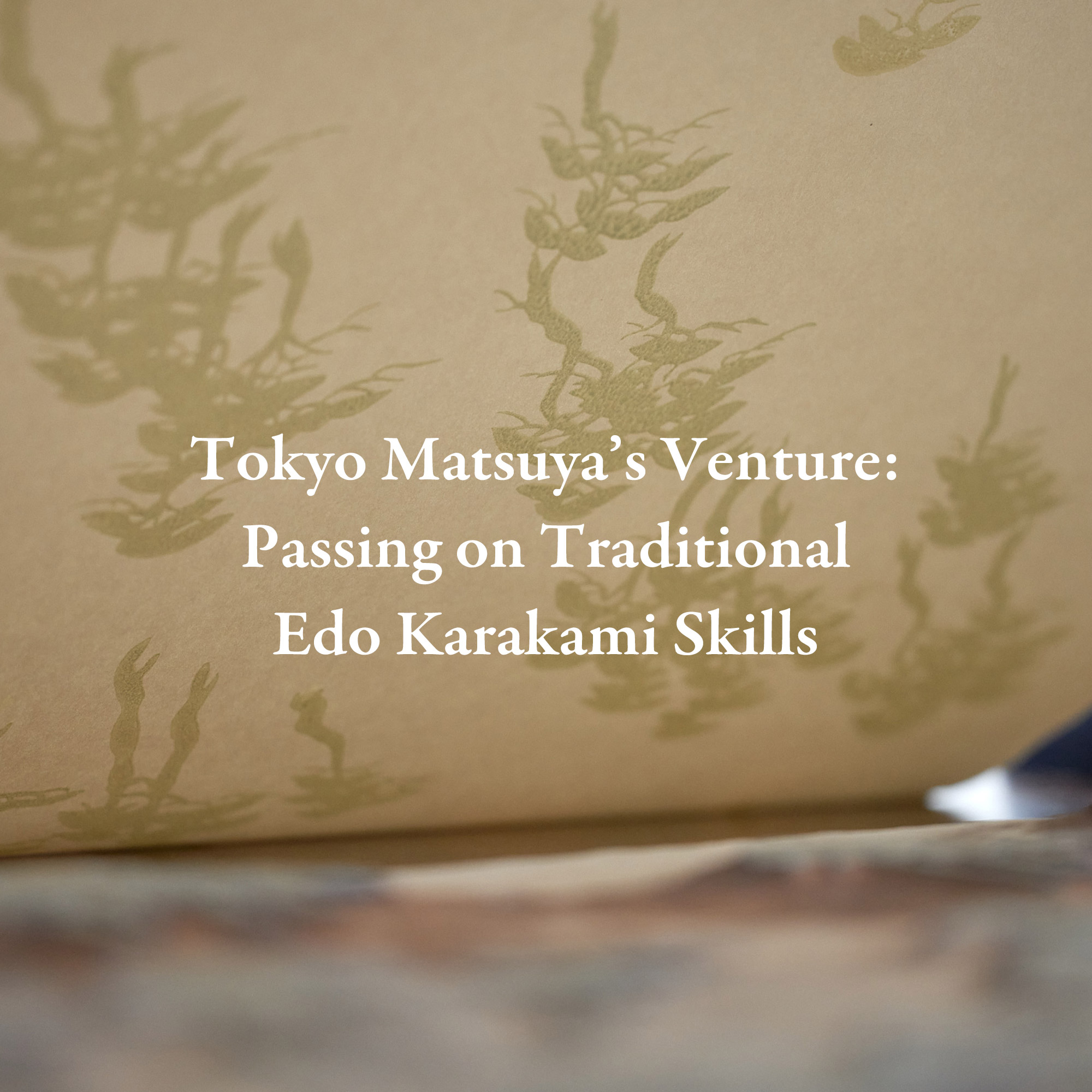

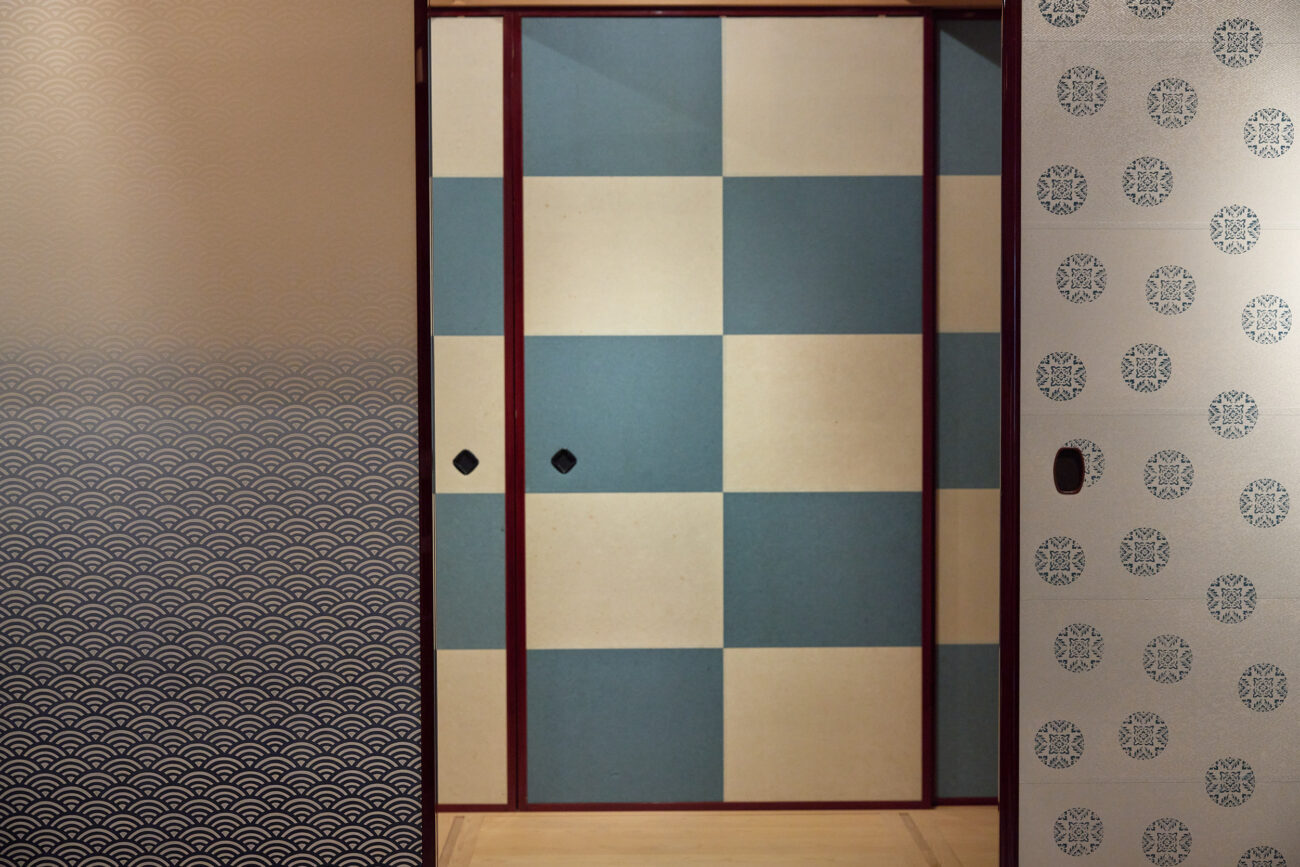

Tokyo Matsuya, a washi wholesaler founded in 1690 and based in Higashi Ueno, Tokyo, is also the “publisher” and owner (hanmoto) of the carved woodblocks used for producing Edo karakami. Karakami is patterned washi used for mounting scrolls and covering screens, partition panels, and other interior furnishings. Tokyo Matsuya has played a leading role in reviving traditional karakami, which had been on the verge of dying out. Since the designation of Edo karakami as a traditional art craft by the national government in 1999, it has enjoyed a resurgence. Thanks to extensive media coverage since then, it has captured the interest of architects as an interior-decoration material, and demand for papering fusuma sliding panels and for use in stationery items and lighting fixtures has been growing.

At a glance, this appears like tremendous progress, but the craft’s future is not necessarily rosy, given that artisans are aging and many workshops have gone out of the business in the past decade. Recognizing that a craft with a centuries-long history might die out, Tokyo Matsuya decided to bring in house all the previously outsourced processes.

The Past and Present of Edo Karakami

Edo karakami evolved from Kyoto karakami, which used carved woodblocks to print designs onto washi. Edo karakami employs a variety of techniques such as sarasa stencil dyeing; chojihiki striped-pattern dyeing using a brush with bristles removed at intervals to create a striped pattern; and sunago using gold or silver foil or flecks to create decorative patterns on washi. Karakami techniques and designs originated in China and the paper was first imported into Japan during the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127). The beautiful kara no kami (paper from “Tang,” which became the general term for China in early times) was highly prized by Heian period (794–1185) aristocrats, and domestic production eventually began. Heian nobles used handmade decorative papers called ryoshi for writing waka poems or copying sutras; karakami is a sub-genre of that type of paper. Elegant karakami printed with auspicious designs using mica or gofun (coating made with crushed seashells) applied with woodblocks gradually started being used on fusuma sliding panels, walls, or other interior surfaces and eventually spread from Kyoto to the entire country.

Edo karakami gained in popularity as decorative paper for fusuma in the residences of daimyo and wealthy merchants in Edo (present-day Tokyo) after the establishment there of the government of the Tokugawa shoguns. But Edo was ravaged by frequent fires, which destroyed not only houses but also the carved woodblocks used to print karakami designs. Artisans thus had difficulty keeping up with new orders. They came to realize that they could repurpose the shibu-katagami paper stencils used to print fabric for samurai formal wear (kamishimo), kimono, and yukata in lieu of woodblocks to produce single- or multicolored designs on washi, giving rise to the stencil-dyeing method. Other Edo karakami techniques included chojihiki striped-pattern dyeing, using brushes to rub the washi and create designs with greater depth; sunago, a decorative technique using gold or silver foil or flakes to create abstract patterns similar to those of Heian period ryoshi; or a combination of different techniques to create karakami in distinctively Edo style.

Traditional karakami was used to cover fusuma panels by pasting together twelve sheets of koban-sized 30 x 45-centimeter washi. By the Kyoho era (1716–1736) midway through the Edo period, such a wide variety of patterns for karakami had been created that they were dubbed the “Kyoho thousand patterns.” In the fires that devastated Tokyo following the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, however, most of the carved woodblocks used to create those patterns were lost. Later, washi makers became able to produce paper in large (oban-sized) single sheets for fusuma measuring 91 x 182 centimeters and new blocks were carved to accommodate the larger size of paper. But rather than producing patterns by pasting together twelve sheets, the carved woodblocks or paper stencils were applied successively to create repeating motifs. This became the technique used for Edo karakami, which made larger, more relaxed patterns and empty space possible and produced the clean, streamlined look preferred by Tokyo-ites.

The losses from the 1923 earthquake were not the end of the trials faced by Edo karakami. The firebombing of Tokyo at the end of World War II reduced to ashes the lower areas of the city (shitamachi), where many artisans lived, and again many printing blocks and paper stencils were lost. During postwar reconstruction and the rapid economic growth period of the 1960s, Edo karakami was eclipsed by cheap, industrially produced fusuma paper. By 1963, when Tokyo Matsuya’s 18th-generation head Ban Rihei took charge, most of the company’s products were also mass produced by machine. Rihei’s daughter Kono Ayako, who heads product planning and public relations at the Matsuya showroom, relates that her desire to revive the beautiful traditional ornamental washi gained momentum after seeing an old sample book that had been preserved in her father’s home. Rounding up artisans with the required skills, she had the printing blocks and stencils reproduced and restored, a process that took thirty years, until 1992. Since then, another thirty years have passed, ushering in a new era of change.

In-house Work by Multi-skilled Artisans

As explained above, producing Edo karakami involves processes using carved woodblocks and stencils, striped-pattern dyeing, and application of decorative flakes and powders. This work was formerly divided up among different artisans: the karakami-shi woodblock printers who specialized in printing using woodblocks and chojihiki striped-pattern dyeing, the sarasa-shi (patterned cotton fabric) stencil-dyers, and the sunago-shi who were in charge of applying decorative finishes. More than twenty years ago, I visited four workshops engaged in those processes, but some ten years or so later, the sarasa-shi stencil-dyer’s business had closed. This prompted Tokyo Matsuya, with the future of Edo karakami in mind, to begin shifting the production processes in-house. There are currently five employees who make Edo karakami at Tokyo Matsuya, headed by Takasugi Yuya, an 18-year veteran. He relates that when he began his career, he was in charge of producing lamps, lighting fixtures, and other items made using Edo karakami. In those days, there were still many artisans working with Edo karakami.

A turning point for Takasugi came in his fifth year with the company, when he was sent to a training school for scroll and fusuma mounters (hyogu-shi) run by a hyogu-shi cooperative. “The training school still had places left to fill for the hyogu-shi course, and the cooperative approached Tokyo Matsuya, which sent me there.” The work of mounting involves handling washi paper, and Takasugi believed that he could profit from the training. That is where he acquired the full range of skills required to mount scrolls as well as cover fusuma and shoji panels.

Tokyo Matsuya is in the process of setting up a system that will enable it to carry out all the processes for creating Edo karakami. Takasugi handles both woodblock printing and sarasa stencil dyeing, while traditional artisan Akita Hideo, whom I will introduce on another occasion, does the sunago decorative finishing work. Kono Ayako praises Akita’s skill, saying “His work is very polished and cleanly finished. The question now is whether productivity can be boosted, but for the sake of our customers, quality comes first.” Right now, one of the two woodblock printer workshops has closed, and at another workshop handling chojihiki striped-pattern dyeing, the senior artisan passed away. His successor, thinking of the future, has begun training Takasugi in this dyeing technique. Thus, Tokyo Matsuya has taken on the work previously handled by three different workshops. It is hard work and a heavy responsibility, but as long as there is someone to master the required skills, these can be passed on to the next generation. In the world of traditional crafts, there is always the awareness that, for lack of artisans, a particular skill may die out, and Takasugi and his fellow workers at Tokyo Matsuya are surely working with that in mind.

Now I would like to describe the woodblock printing and sarasa stencil dyeing carried out by Takasugi and his fellow artisans. They are working to preserve the legacy of Edo karakami, relying on past records, guidance from senior artisans, and their own distinctive skills.

The Skills of the Karakami-shi—Woodblock Printing

The wood printing block is the large size, matching the width of the Echizen washi used as standard fusuma paper. The block is fixed in place and the paper laid over it to imprint the pattern. The artisan explains that “a same-size piece of wood will inevitably shrink or warp, and the pattern can easily shift out of place over the uneven parts, making exact matching difficult. That’s why we choose designs that don’t need matching.” Cherry or katsura wood has been used for the printing blocks up to now, but nowadays it is rare to find trees large enough to yield slabs of the required size. “I suppose we will have to accept that we’ll need to use joined blocks in the future.” Today, all kinds of traditional crafts experience the same difficulty in obtaining suitable materials.

The mica used for kirazuri is a silicate mineral crushed into a powder. It creates shimmering motifs in woodblock-printed karakami that shift depending on the light. The mica is blended with soil-based pigment (suihi enogu), as is also done for Nihonga-style painting. But as neither mica nor soil-based pigments are soluble and mica, in particular, tends to sink, funori glue is added to the mixture to evenly distribute the mica. To increase adhesion, nikawa glue and rice starch glue are also added. The specific amounts of each of these ingredients must be adjusted depending on the weather and humidity, and Takasugi notes the amounts in each case to keep a record of the proportions used and add to his depth of experience.

The color thus prepared is brushed onto a frame over which thin silk has been stretched and applied carefully to the carved wooden block. Screens of this kind are harder to obtain than before, and Takasugi, wondering what could serve as a substitute, suddenly remembered French embroidery hoops, which he repurposed in a bit of do-it-yourself adaptation.

He is now using this tool together with a screen passed on by a senior artisan. Different fabric is stretched over the frame depending on the motif’s degree of detail; thinner fabric is used for more finely detailed motifs.

Now comes the actual printing. The washi is carefully laid onto the woodblock and gently stroked with the palms of both hands. The arms are moved in a motion like “swimming” (oyoginade), which makes it easier for the hands to glide over the paper. Artisans I previously interviewed now and then placed the palms of their hands against their cheeks, using the skin’s oil as a lubricant. When I asked Takasugi what he did, he said he carried ibota border privet wax in the pocket of his apron. Ibota wax, secreted by parasites on the plant, is also used to make hanging scrolls slide more easily, knowledge that Takasugi gained through his work in paper mounting.

A softly detailed motif is revealed when the washi is lifted from the woodblock. Mechanical printing can never achieve the subtle lines and the slight unevenness inherent in the process, which highlights the qualities of the materials.

The karakami woodblock printing process can also be viewed in this video (Japanese language only).

The Skills of the Sarasa-shi—Stencil Dyeing

The sarasa-shi stencil dyer uses shibugami stencils made of sheets of washi paper coated with persimmon tannin and then smoked and dried, and onto which patterns are cut with an etching knife. These stencils are used to create Edo-komon, nagaita chugata, wa-sarasa, bingata, and other patterns for dyeing the textiles from which traditional Japanese clothing is made. Multiple stencils can be used for multicolor printing, but this time I was shown how the sarasa-shi artisans use a single stencil and add a shading effect. They used a large stencil sized to fit 91 x 182 centimeter-size washi. Two artisans apply the dye together with round deer-hair brushes, working from each side of the stencil. These brushes are another hard-to-come-by tool that are ordered specially from Kyoto.

Shading is carried out by two artisans. One uses a regular writing brush to outline the edge of the motif with color, and the other follows with a wet brush to dilute the color, causing it to blur over the flower petal motif already printed on the paper. A slight reddish tint appears, for a subtle expression of color. Which petals get the shading treatment is left up to the artisan’s sensibility.

The stencils Takasugi and other artisans were using were bought from a stencil dyeing studio that had to close, and they are showing their age. Like all the other tools of the craft, stencils are used with care, but they are consumables to begin with, so there is a limit to how long they last. Torn or frayed edges are repaired with washi tape or a similar handy item.

When I previously saw a stencil dyeing artisan at work, he would take a swig of water from a bottle and spurt it out in a fine spray to moisten the stencil. As a child, I would see a neighborhood tatami mat maker do the same, so the sight brought back memories. Moistening the paper that way is no longer done, though, as it is considered unsanitary, and Takasugi himself uses a sprayer. The shibugami stencils are kept moist, but fewer and fewer stencils are being produced nowadays, and Takasugi expects that they will eventually be replaced by synthetic paper, eliminating the need for any spraying at all.

The motifs created with stencil dyeing are smooth and sharp thanks to the materials used in the process. Like patterns made with woodblock printing, earth-based suihi enogu coloring is used, but the adhesives are nikawa glue and thick kon’nyaku glue, which leaves a smooth surface when it dries. The sarasa stencil dyeing printing process can also be viewed in this video (Japanese language only).

Mounting Skills Support Traditional Techniques

Both woodblock printing and stencil dyeing necessitate applying an undercoat. A brush soaked in pigment or paint is run across a large sheet of washi, which is then dried. Next, the washi is decorated, but the entire sheet needs to be moistened first. That is necessary in order to flatten the paper and assure that the printed patterns will adhere properly. Takasugi wets the paper with a brush and then places it in a plastic bag, to ensure that the paper is moistened evenly; otherwise, some spots will be too wet while others will be too dry. Placing the paper in a plastic bag traps the moisture, dampening the paper evenly. “When washi is pasted onto shoji screens, the glue is applied to the frame and the crosspieces, right? Washi that is dry is stiff and unwieldy, so it’s hard to apply. Before mounting, it is moistened with a sprayer or a wet brush. I learned when I was in training as a mounter to moisten the washi and place it in a plastic bag in the morning so that it moistens evenly, and to use it for mounting in the afternoon, and I’m using the same technique for karakami.”

Compared to the natural materials used in the past, modern conveniences like plastic play a useful role in art crafts by helping boost efficiency. There is no need to do everything exactly like it was done in the past; I also feel it is meaningless to expect artisans to do so. But how did woodblock print and stencil dyers handle this step previously, without using plastic? Apparently, they would let the washi sit while they took a cigarette break, and then proceeded with decorating the paper. Smoking was part and parcel of artisans’ life in those days, although things are different nowadays.

Tokyo Matsuya

Address:

Tokyo Matsuya Unity, 6-1-3 Higashi Ueno, Taito-ku, Tokyo 110-0015

Tel. (03) 3842-3785; fax (03)3842-3820

Hours: 9:00 am–5:00 pm (closed Sundays and public holidays)

https://www.tokyomatsuya.co.jp

https://www.tokyomatsuya.co.jp/en/edokarakami.html (English)