Page Index

In this series we introduce people who are engaged with children’s learning and learning environments, focusing on their ideas and aspirations. What should be done so that children’s learning will be lively and animated and so that they will grasp the fascination, beauty, and importance of traditional crafts? Based on the issues she faces in communicating her own field, the author will ask her interviewees the questions she herself would like to ask about their work, and share the perspectives she gains in communicating her own field to others.

The Horniman Museum and Gardens in Forest Hill is less than one hour by train from the center of London. The museum has a history of 120 years and boasts a collection of more than 350,000 items from cultural artifacts from countries all over the world to curiosities of nature. It is the perfect place to step into all kinds of worlds and study what is found there. The museum is well-known for its large collection of stuffed animals, its aquarium, and its 16-acre garden with fine views of the London skyline in the distance.

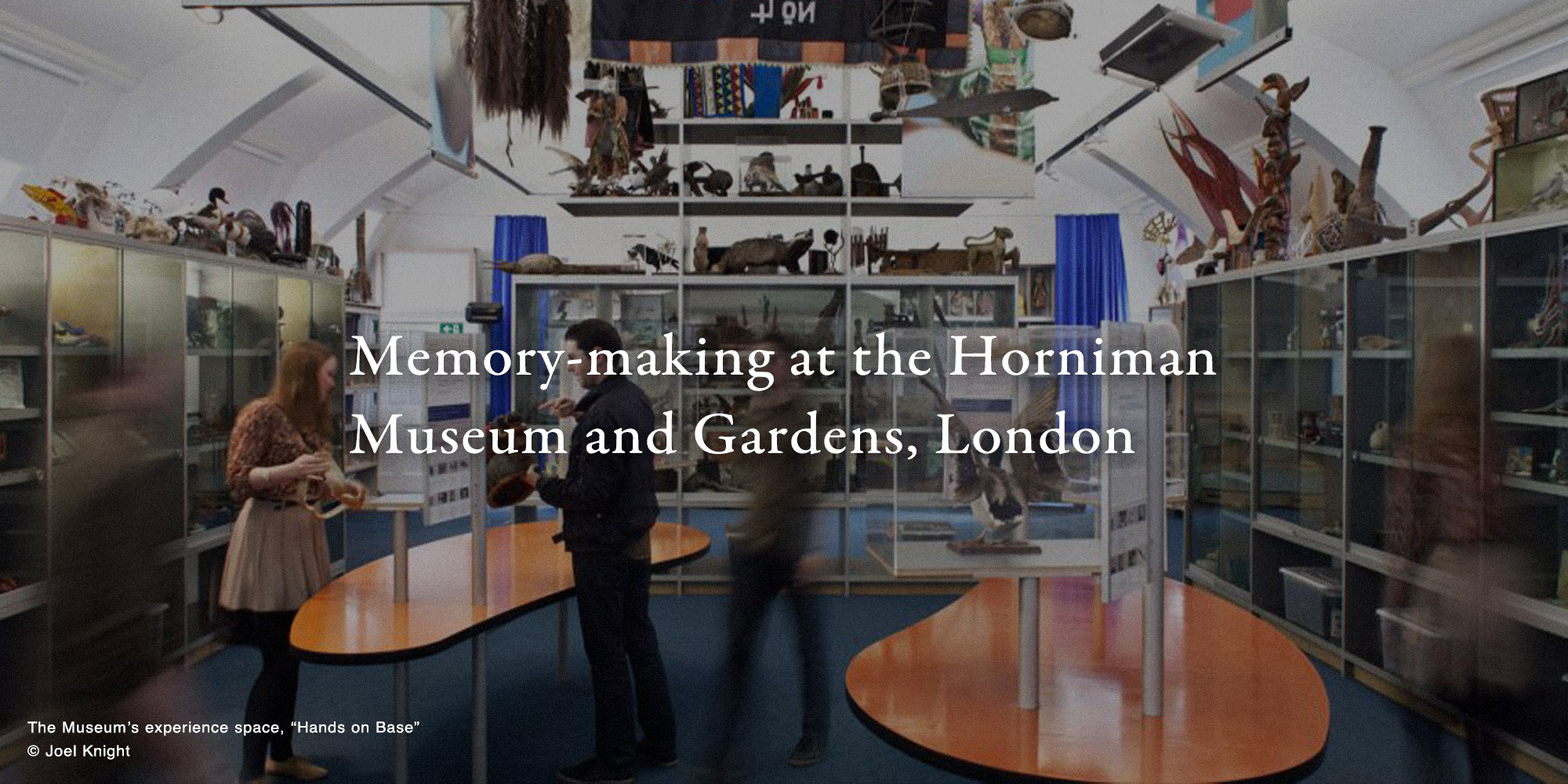

I would like to introduce the museum’s Hands On Base, something that few other museums offer, where visitors learn by handling objects. Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, the space was open to the general public daily on weekdays but is now open only on Thursday afternoons. On the other weekdays, the space is reserved for visits by school and community groups, who use it for lessons or projects.

The Hands on Base is surrounded on all four sides by glass cases displaying everything from fossils and musical instruments to seeds, industrial products, and other objects from all parts of the world. Folk masks, dolls, and animal skeletons hang from the ceiling. The moment anyone enters here, the endless possibilities for exploration stimulate their curiosity.

Museum employees Lucy Maycock and India Patel work in the museum’s Formal Learning Team, and manage the care of the Handling Collection. Interacting with visitors of all ages, they are experts at stimulating learning and aim to teach every individual how to develop connections with objects through handling. I asked them about their workshops on learning through handling.

© Horniman Museum and Gardens

Lucy Maycock

Lucy Maycock is the Formal Learning Manager at Horniman Museum and Gardens. Lucy has worked at the Horniman Museum in various roles for the last seven and a half years. She is passionate about object-based learning, co-creating programmes with communities.

© Horniman Museum and Gardens

India Patel

India Patel is the Formal Learning and Handling Collection Assistant at Horniman Museum and Gardens. India is interested in researching ethical practice surrounding Handling Collections and how they can be used to open up museum collections by creating meaningful interactions with objects.

The Handling Collections consist of 3,500 items. A selection of curated objects is displayed on the shelves, but none are captioned. Great value is placed on having individuals establish a connection with a particular object, and commentary that could create any biased interpretation is avoided.

Creating connections with objects can happen through hands-on experience learning which Lucy describes a “proper memory-making.” She related her own experience with the importance of handling objects.

“I work at a museum today because I had the opportunity to handle an ancient Egyptian object when I visited a museum as a child with a school group. But even twenty-five years on, I clearly remember that experience. I remember how special it was to touch an object that was so closely connected to something I was really interested in.”

Communicating through Objects

Based on personal experience, Lucy believes that handling an object enables the person to absorb information about it and talk about it. “Many people see museums as hard to approach. They believe that they will not be able to understand the objects on display if they lack knowledge and so cannot say anything about them. It’s something that children and adults alike feel.”

Lucy says, “The Hands on Base has changed perceptions, from a museum being a place where people don’t feel welcome to a place that stimulates curiosity and imagination. It’s very empowering to give a child something and trust them to hold it. … A child might think, ‘this is cold to the touch,’ or ‘this is heavier than I thought it would be,’ or ‘this is lighter than I thought it would be’ or ‘this feels amazingly delicate.’ And that’s going to affect how they’re holding it and maybe change how they see this object and change their mood and their experience, because now they’re holding something where they need to be extremely careful. I think just that in itself is such an important thing, regardless of what the object is, where it comes from, what its meaning is, how any of that, just that experience of holding something is extremely powerful.”

India adds that “the point is not how many objects you touch, but focus on touching one particular object and taking time to observe it. I think it’s also how you set up the experience as well, because we have so many objects in this room that pulling everything out would be quite overwhelming. But if you have a group of objects, or just a few, then it becomes easier to absorb extra information, but also just spending time sitting with the objects. But just being able to really sit and have time with just a few objects, I think, is really special.”

When I visited the Museum, many parents and children were sitting on the floor, looking at each object in turn, discussing what they might be or what they are for. It was interesting to me to see how children’s curiosity flowed and developed.

Discovery Box

Just as people establish connections with objects, they can also develop relationships with people through objects. Take the Discovery Box, for example.These boxes were developed during the 2018 relaunch of the World Gallery, which explores the fundamental question of “what does it mean to be human?” Each of the boxes contains themed objects selected by different community groups and, in effect, constitutes a mini-museum.

The boxes are plastic storage containers containing layer upon layer of objects selected. Each box is labeled with an explanation by the community group that chose the objects it contains, the theme selected, reasons for selecting the items, and questions about them.

For example, the “Rewrite” group, which connects young people through the power of creative art and fights prejudice and unfairness, created a “survival kit” for people landing on a new planet. Thinking what a person, having left behind all possessions and comforts, would need to make a life in a new place, they chose objects including a compass, seeds, a clock, bags and containers for carrying food, and a yoyo for entertainment.

The groups Mental Health NHS and DACT, a community of deaf people, created a box containing objects to help deepen understanding of people with hearing disabilities. The objects included a butterfly, because many butterflies cannot hear sounds and their flight is guided by vibrations they detect with their feelers; a comedian mask with an exaggerated facial expression, given the importance to deaf people of facial expressions and eye contact to communicate; and a whale eardrum, to understand the structure of the ear.

But the Discovery Boxes are not often used in the learning programmes and projects. They are used mainly by visitors to the Hands on Base, who voluntarily interact with the contents, but they are also useful for easing the tension at the beginning of a session.

Connections with Communities and Schools

India thinks that a museum is not only a venue for displaying objects; it should also connect with the community involved with that object. I was also impressed by her understanding that young people learning through the museum’s collections works two ways.

“We get students in museum studies, anthropology, and art, because London has so many fine arts universities and vocational colleges. But last year, we had engineering students come, who were interested in 3D scanning, and we discussed schools and the collection. I had never worked with students in the sciences before, but it was a valuable experience and really interesting because it made me think about the different ways in which we can use our collections in different areas of study.”

Lucy continues, “There are also children who can’t attend school, due to a medical condition or lack of support at school. These home-educated children, whose numbers have been growing since the pandemic, can take lessons at a museum, and we have a programme that we’ve been expanding and trying to refine. What was formerly the Schools Team is now the Formal Learning Team, because we work with a wider audience in schools, and because we do more and more work with home-educated children in particular, who are out of school settings, so we wanted that to be reflected in our programming.”

Exploring for Themselves

Touching and handling are important elements for deepening learning. On the other hand, breakage is always a risk. I asked Lucy and India what they do in such cases.

India explains, “We have a community engagement assistant who takes care of all the repairs with a team of three or four volunteers. If repairs are more specialized, we might call on a conservator to repair an ancient Egyptian object or a taxidermist to repair a stuffed object. But then we’ll go into a session and objects break almost immediately, because they haven’t been fixed to be handled. Our repairs aren’t beautiful and perfect; they’re more about making sure that an object isn’t going to break the first time it’s used.”

It’s also important that covservation restoration methods and materials be appropriate for the intended purpose. It seems to me that the Hands on Base works because the objects displayed have been carefully chosen with an eye to whether repairing is possible or necessary.

I also found it interesting that the objects that break do not look that delicate. In other words, objects that look and are actually fragile don’t often get damaged. If children are told that something needs to be handled carefully, and placed on a cushion or handed over with care, they will handle it with great care and respect.

During a session, Lucy takes care not to give too many hints or clues ahead of time, but to let the children explore for themselves. She says that moments like that are what she finds most rewarding about her work. “They’ve just looked at that object, really thought about it, and come up with something. And that’s what everyone should be doing if the session was really successful.”

“Occasionally, you’ll get a workshop where a child will say something about an object that other children haven’t said before. I’ve been here eight years; I’ve heard a lot of things said about the same objects, but very occasionally, a child will say something new.”

Creating Connections with Objects

Lucy and India lead lessons and workshops encouraging children to bring their own perspectives to the objects they have handled. They also described online workshops on traditional cultures and crafts. India says, “we did kind of a virtual workshop in which we had puppet-makers in northern India who have continued for generations and artisans who make textile flowers showing on screen, while we were here in the Museum trying to do the same thing, as you might do in a cooking class.”

The museum is planning to use a recording of the session for other activities, upload it to its website, and make it available for people to see how the crafts are made. It has also purchased materials showing how the crafts are constructed and the various steps involved in making the objects.

Lucy and India also mentioned individuals using TikTok to demonstrate traditional crafts and said that they follow TikTok videos that show Japan’s traditional craft of metal hammering to make tea kettles.

Lucy added that “it will be interesting to see the impact of slowing down and stopping, and being made to make things to pass the time, and then how suddenly people realize how good that can be for your wellbeing.”

Many of Japan’s traditional crafts are made for utility; in other words, they are made to be handled. On my visit to Horniman, I learned that at this museum, adults and children alike, are “learning to learn” by experiencing objects from various perspectives and creating connections that become deeply rooted in their hearts and memories.

Interview cooperation

Horniman Museum & Gardens

100 London Road, Forest Hill, London SE23 3PQ

Tel 020 8699 1872

https://www.horniman.ac.uk